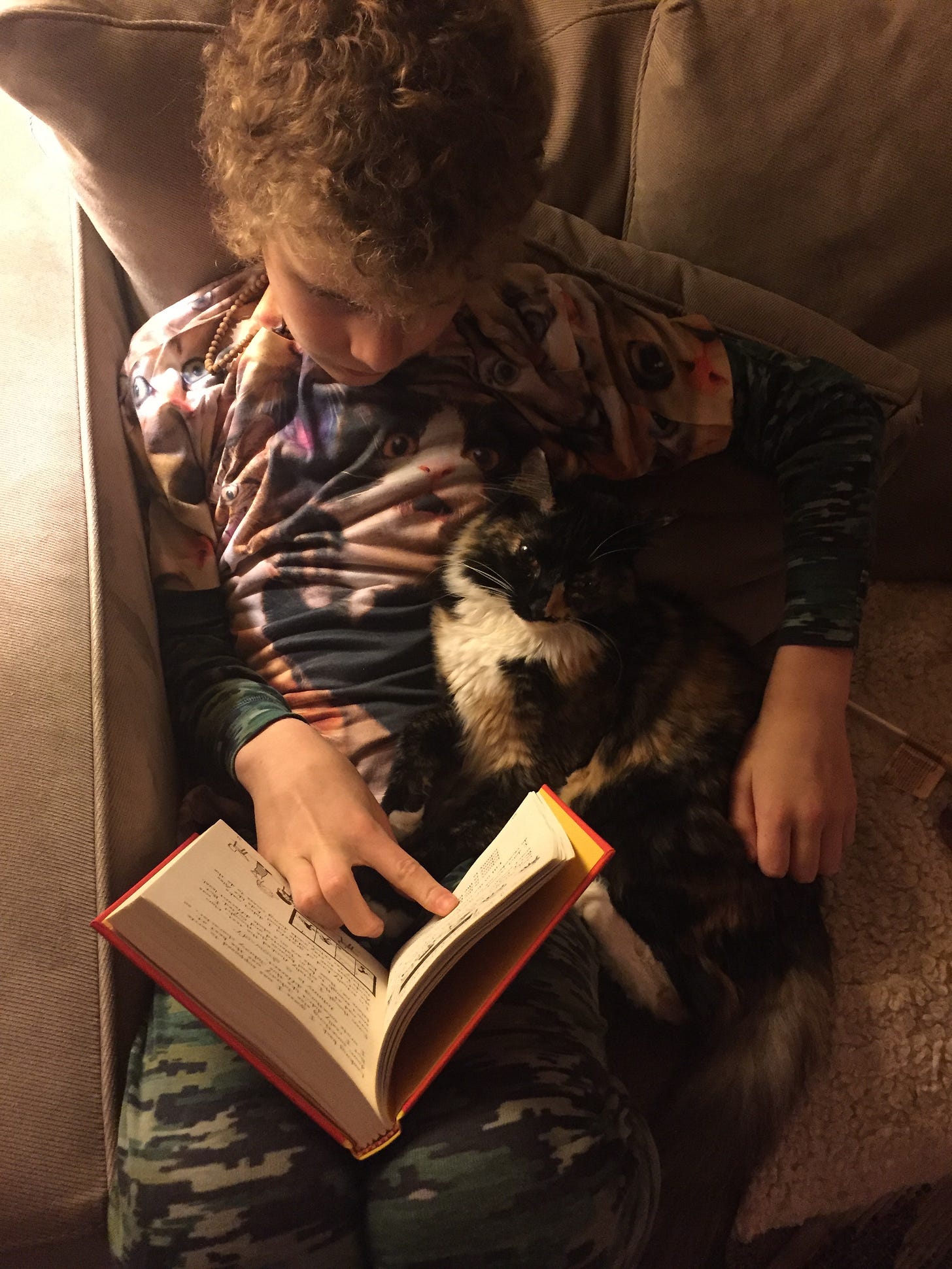

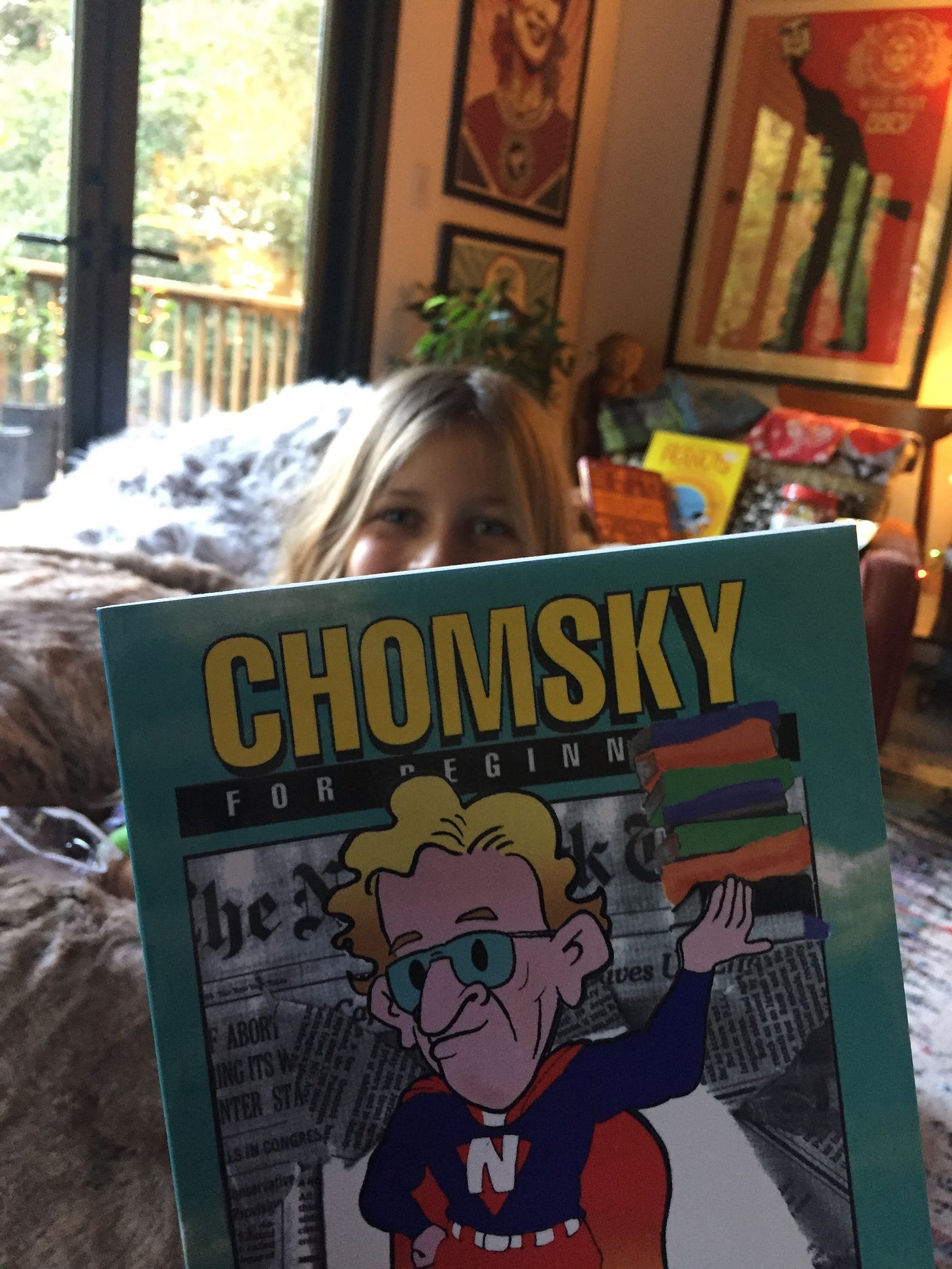

The hierarchy of attention has inverted. Television plays in the background while we scroll. Books lie dormant in our laps. The New Yorker, once a bedside companion, has been replaced by an infinite scroll of ephemera. What was once secondary has become primary, and what was primary barely registers at all.

This inversion represents more than a shift in habits. It marks a fundamental reorganization of human thought patterns. Working memory, once developed through necessity - service industry orders, classroom note-taking, sustained reading - now exists primarily in external storage. Our phones remember, so we don't have to.

The human brain processes information through multiple distinct languages. A musician in flow state activates neural pathways different from a mathematician solving equations or a gamer navigating complex social architectures online. Each mode of expression - dance, code, chess moves, whiteboard diagrams - represents not just a skill but a complete system of thought, a way of processing and generating meaning.

Consider the institutional implications. Consulting firms deploy recent graduates to provide expertise they haven't earned, armed with recycled slide decks rather than lived experience. This isn't just inefficient - it represents the systematic devaluation of deep knowledge in favor of quick synthesis. The same pattern appears in journalism, where nuanced analysis gives way to reactive headlines and submissions are no longer accepted from unknown authors. Even in education, where depth of understanding yields to breadth of coverage.

Flow states - those moments of deep engagement where time dissolves and creation feels effortless - require specific conditions. A guitarist in the studio, a coder at her terminal, a philosopher at her whiteboard - each finds their flow through different channels. These aren't just productive states; they're generative ones, creating new neural connections, new possibilities for thought.

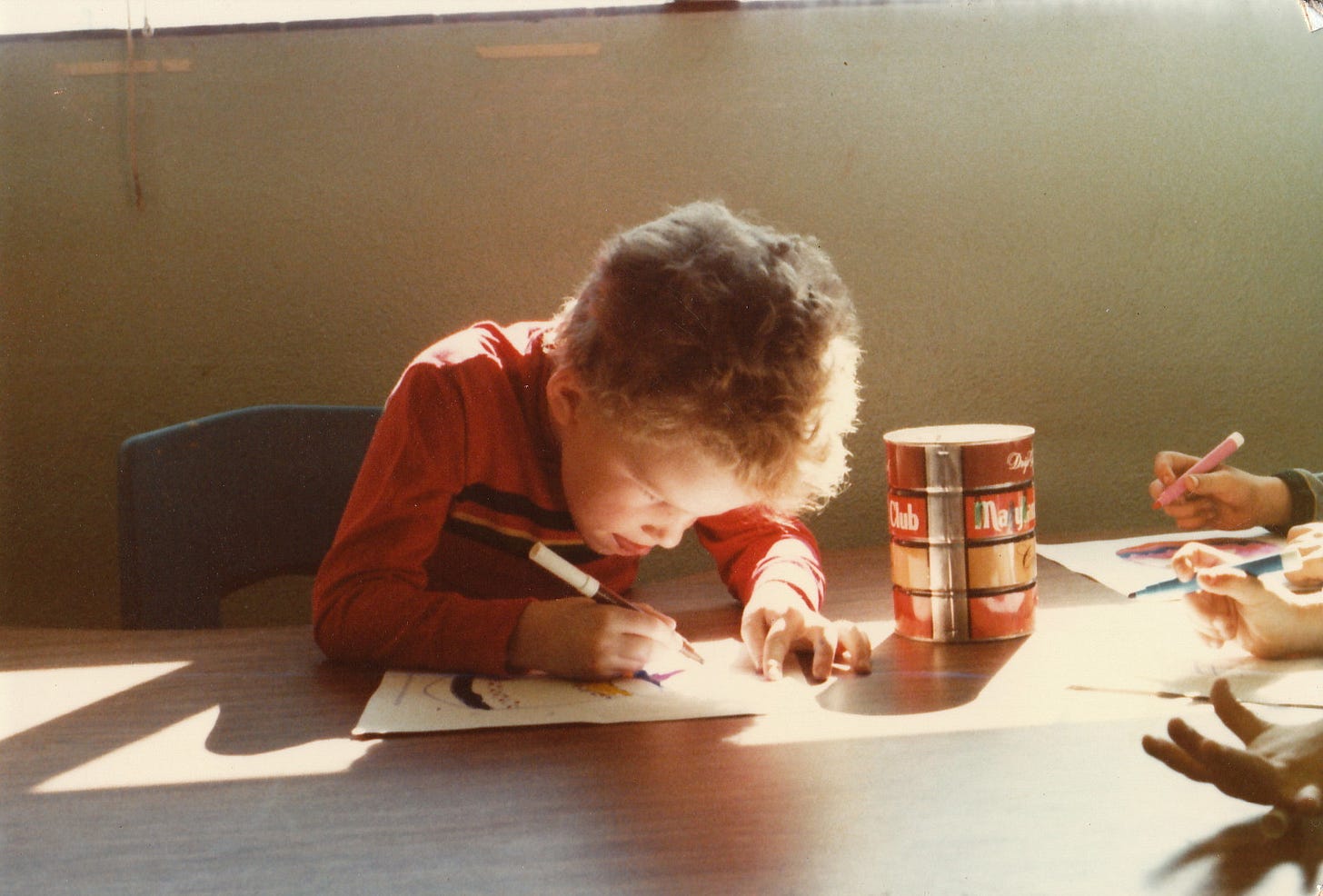

The written word itself is not as simple as writing and reading, the modalities matter. Handwriting engages different cognitive processes than typing, which differs again from thumb-typing on phones. Reading activates different pathways than listening. Speaking demands different mental architecture than writing. Listening to an podcast is different than an audiobook, audiobook of fiction different than one on history. Each mode shapes not just how we communicate, but how we think.

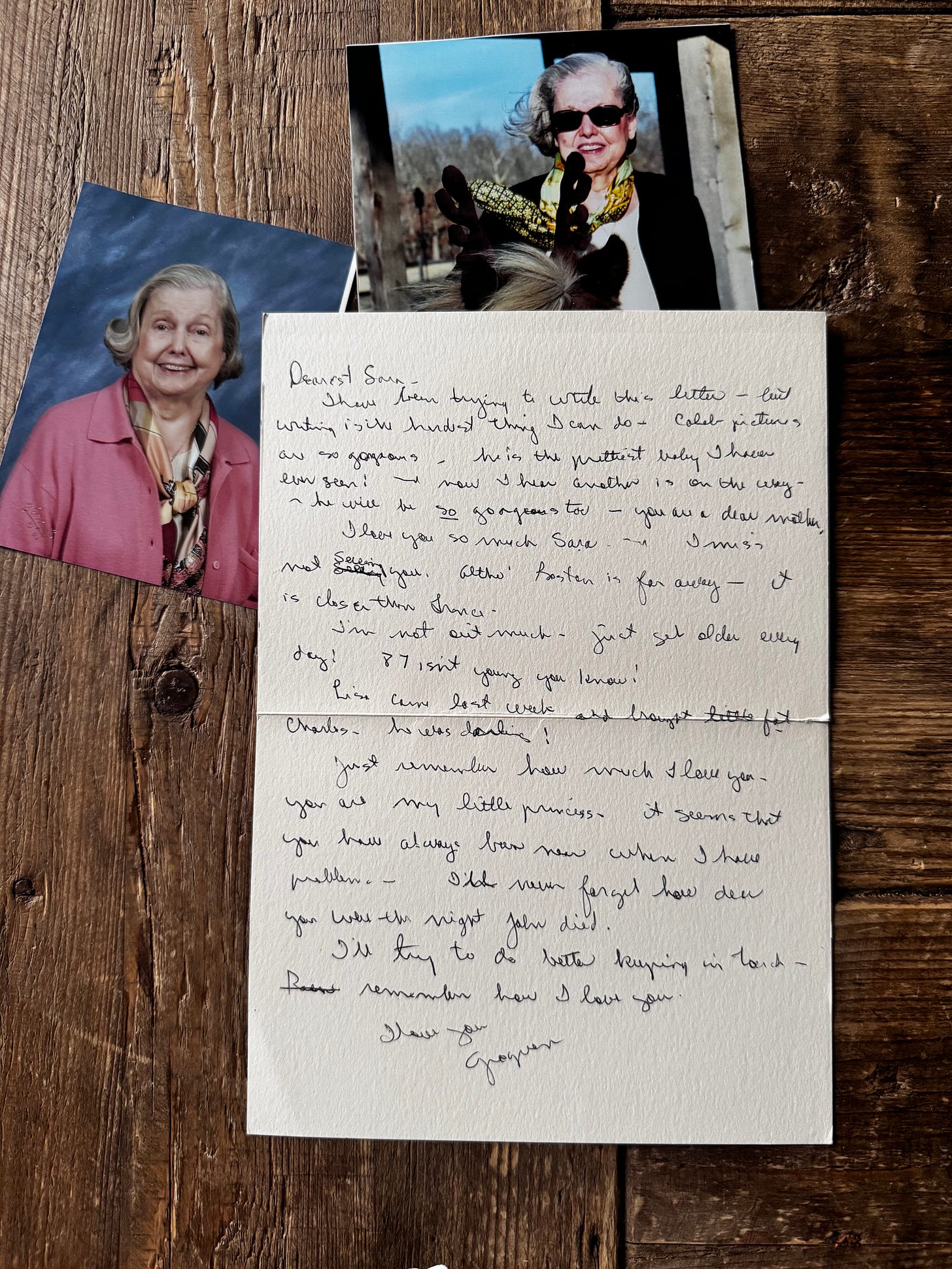

The accumulation of human knowledge flows through these various channels as well. Aspasia's teachings, preserved only through her students such as Socrates’s memories, remind us that influence need not be written to be profound. Yet the systematic preservation of thought - through correspondence, through documentation, through careful analysis - builds frameworks for understanding that span generations.

The modern communication paradigm fragments our system of thought preservation. Voice notes dissolve into digital ether. Lengthy messages meet with hostility or indifference. Phone calls require advance scheduling, and even then, attention splits between conversation and screen. We share physical space while inhabiting entirely different universes of thought.

This isn't nostalgia for handwritten letters or leather-bound books. It's an examination of what happens to human cognition when we narrow our expressive channels. When we optimize for speed over understanding, for reaction over reflection, for content consumption over content creation. It is impossible to know which conversations we aren’t able to have that would be more valuable.

The solution lies not in rejecting digital tools but in understanding how different modes of expression serve different cognitive needs. Reading deeply. Writing thoughtfully. Moving our bodies. Making music. Solving equations. Gaming with purpose. Each activity exercises different mental muscles, builds different architectures for understanding and connection.

The future of human thought depends not on choosing between digital efficiency and deep engagement, but on maintaining fluency in multiple languages of cognition. The medium shapes not just the message but the mind itself. In ceding certain channels of expression, we risk losing not just ways of communicating, but ways of thinking.

What's at stake isn't the art of letter writing or the pleasure of sustained reading. It's the human capacity for generating new thought, for achieving states of flow, for building understanding that transcends the immediate and ephemeral. The question isn't whether we'll continue to communicate, but whether we'll maintain the neural architecture necessary for deep thought and genuine innovation.